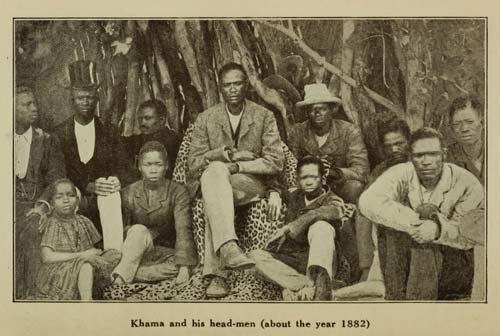

Start of Khama's Rule

Khama and his brother Kgamane had been very close, but during this period there were bitter arguments as Khama believed his father was favouring his brother Kgamane. Unable to live with them, Khama left to stay near modern day Serowe and later Moteti, where he was followed by many of the Bangwato people, and in 1874 the population of Shoshong dropped as low as 4,000. [1]

Eventually Sekgoma sent Kgamane to beg his brother Khama to return.

� he went with Mr Mackenzie and Mr Hepburn, and entreated Khama not to separate from them. With flashing eyes and infinite sternness, Khama replied to his brother Khamane: �When I lived with you my face was pain to your eyes. You treated me just like a dog in my own lolwapa (house-front), and before my own people; therefore, I refuse to be in the same town with you and Sekhoma. I have had enough of that; let us separate. Do you take your road, and I shall take mine. Those who prefer to remain with you, let them remain; and those who wish to come unto me, let them come.� Khamane and the missionaries then returned to Shoshong. [2]

In 1875 Khama returned and took over the chieftainship with force, and Sekgoma and Kgamane were again forced to flee.

And so at the age of 40, Khama became kgosi and immediately made an impact. Khama stopped beer-drinking, initiations, and made a law against the purchase of slaves. Even the European traders were forced to follow his rulings and those who did not were thrown out of Shoshong.

I fought Lobengula [the Matebele chief] and drove him back, and he never came again, and God who helped me then would help me again. Lobengula never gives me a sleepless night. But to fight against drink is to fight against demons, and not against men. I dread the white man�s drink more than the assegais of the Matabele, which kill men�s bodies, and is quickly over; but drink puts devils into men, and destroys both their souls and their bodies for ever. Its wounds never heal. [3]

In August 1876 he wrote to the British governor of the Cape Colony for protection

I write to you, Sir Henry, in order that your Queen may preserve for me my country, it being in her hands. The Boers are coming into it, and I do not like them. Their actions are cruel among us black people. We are like money, they sell us and our children. I ask Her Majesty to defend me, as she defends all her people. There are three things which distress me very much; war, selling people, and drink. All these things I shall find in the Boers, and it is these things which destroy people to make an end of them in the country. The custom of the Boers has always been to cause people to be sold, and to-day they are still selling people. [4]

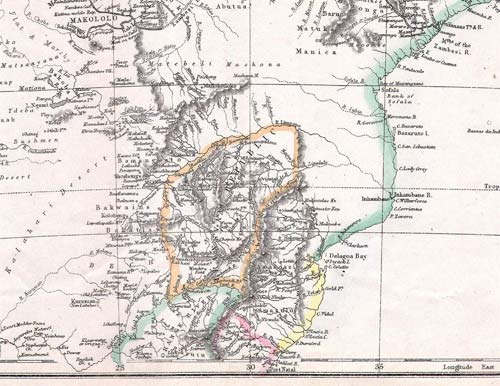

Map of South Central Africa dated 1868 by Edward Weller, which builds heavily on Livingstone�s recordings. The Limpopo through modern Botswana is now broadly correct, although it is wrongly shown discharging into the Indian Ocean at Inhambane.

Rainmakers

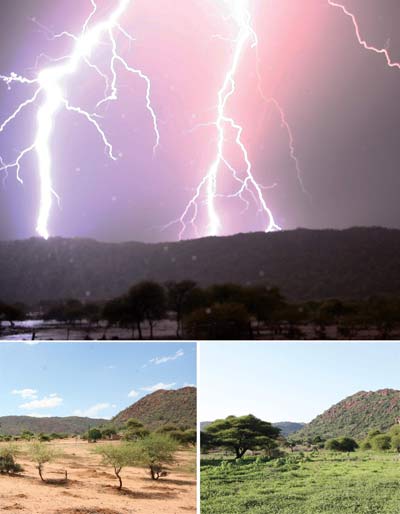

Thunderstorm over the Shoshong hills, and photographs of Shoshong in Nov 2013 and Jan 2014 showing the effect of rainfall.

Water

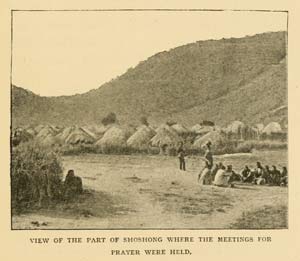

During the dry season, people relied on water from the river valley, where wells can still be found.[On Sundays, Khama] himself always went up early to the springs in the mountain kloof, where the women gathered in hundreds, each with her red or yellow calabash or water-pot to take back the day�s supply. Khama gave them his kindly greeting and a few friendly words as they passed, �Good morning, my friend,� or �my child.� [6]

References

[1] Parsons N (1982) �Settlement in East-Central Botswana circa 1800-1920� (from �Settlement in Botswana� Edited Hitchcock R and Smith M (1982) Botswana Society)[2] Lloyd E (1895) �Three Great African Chiefs, Khame, Sebele and Bathoeng.� T.Fisher Unwin, London

[3,6] Knight-Bruce W (Mrs) (1893) �The Story of an African Chief � Being the Life of Khama.� Kegan, Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co Ltd

[4] http://www.britishempire.co.uk/maproom/ bechuanaland.htm

[5] Hepburn J.D (1895) �Twenty Years in Khama�s Country.� Hodder & Stoughton