Move to Palapye

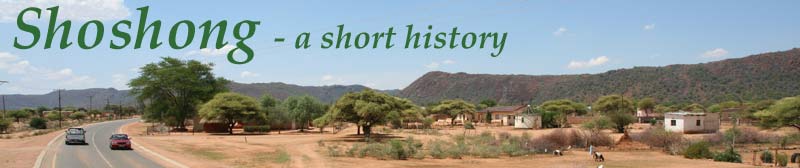

Main photograph of Old Palapye - ruins of Bechuanaland Trading Association store in 2013 © Jacob Knight. Inset photographs by Willoughby (c1895) (Botswana National Archives): Blackbeard’s Store (2 photos), Bechuanaland Trading Assoc Store, and the Telegraph/Post office.

In 1889 Khama and his council decided to move to Phalatswe, which was simplified to “Palapye” by the Europeans. The place is now known as “Old Palapye” to differentiate it from the modern Palapye. The move also affected the other tribes living in Shoshong with the Bangwato such as the Baphaleng, Makalaka, Bakaa, Bakhurutshe, and Mashapatane.

They chose a site sixty miles to the northwest with a lovely range of rocky wooded hills, ample water supply, and fertile soil. Here an allotment of ground was marked out for each man and his family; the big central square and the wide avenues were carefully planned, and the best position of all was set apart for church and missionaries. Then, with hardly a warning, Khama gave the order to move. The well-todo were instructed to lend waggons, oxen, and horses, every one was to help his neighbour, and the big population obediently set out. With its order and disorder, its children, its stuff, and its herds, it must have been a curious picture of a more famous exodus.

On reaching Palapwe the new capital, each man began to build on his appointed ground, till in less than a year there were streets of huts and their enclosures, shaded by trees and in regular order, that covered twenty square miles, and contained a population numbering about 30,000… there are stores for the European traders, blacksmiths’ shops for waggon mending, and a little galvanised iron house, that holds the telegraph office. [1]

In 1890 a correspondent for the Cape Argus newspaper wrote We often speak of Kimberley and Johannesburg as the Americans used to speak of Chicago, as wonderful cities for their age. In my opinion, King Khama’s Bechuana city… is a city not one whit less wonderful than either. Palapye the Wondrous I christen it… 20 square miles of ground holding some 30,000 inhabitants; yet fifteen months ago there was no such place as Palapye in existence!. [2]

Edwin Lloyd wrote rather caustically that “this is the undiluted nonsense written by some journalists”. [3] A trader, Samuel Blackbeard, estimated the population rather lower at around 20,000 in his memoirs. [4]

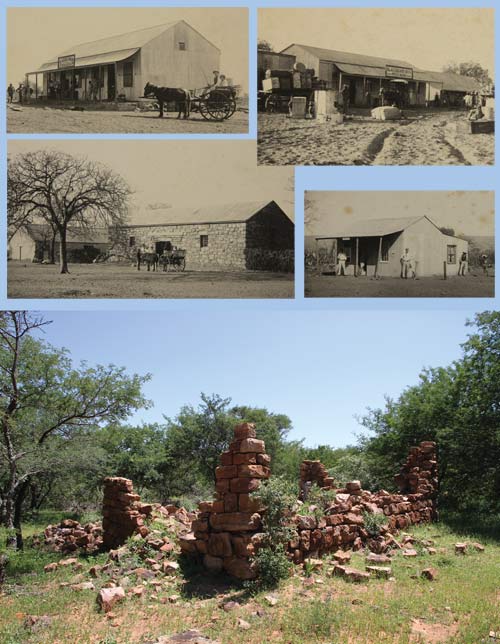

Main photograph of Old Palapye church in 2014 © Jacob Knight. Inset photographs of the church by Willoughby around 1895 (Botswana National Archives).

Hepburn carried on preaching, with weekly congregations numbering as many as 2,000, and he struggled in declining health to build a fitting church for the new capital. The church was never fully finished, but was still a splendid achievement in the circumstances. [6] Parts of the great gable walls still remain, giving a good impression of the size and grandeur of the church.

During this period Hepburn clashed with Khama who saw him as making unreasonable demands such as wanting the Christians to live apart from heathens and to send a mission to the Kalanga living in an area claimed by Khama. As a result of these arguments, Hepburn left in late 1891. He then repented of his haste and returned the following year, but Khama would not see him, and Hepburn returned rather forlornly to England where he died not long afterwards. [7]

In his book, “Khama - The Great African Chief”, John Harris notes that when Hepburn left, Khama sent after him a letter full of affectionate appreciation and regret, and a gift of £1,000 as a token of his regard and personal good-will. [8]

Shoshong was no longer on the main North-South route, but was not completely forgotten. A hunter/naturalist, Henry Bryden wrote in around 1891 ... I met [Strangeways] coming down-country, at Boatlanama, a water on the desert road, between Khama’s old town of Shoshong and Molepolole. In latter days this was not the usual route to and from Palachwe and Matabeleland, but having been several times by the Crocodile road, I happened to have taken the more westerly route for a change. [9]

He describes how giraffe are rapidly disappearing from Southern Africa; A few years since they were to be found at no great distance from Khama’s old capital, Shoshong; now they are first encountered in the bush and forest-region beyond Kanne, or Klaballa, on the way from Shoshong to Lake Ngami. This waterless tract, well called thirst-land, serves them as a safe retreat. From Kanne to the Botletli River, and thence halfway to the lake, Khama reserves them for his own and his people’s hunting, and Dutch hunters, with their wasteful methods, are not permitted — a very wise precaution.

Bryden also notes how accessible the area is now; From Palachwe to Vryburg… (420 miles), is but 20 day’s journey, even by the slow moving ox-waggon. From Vryburg to Cape Town the journey now occupies by rail two days and nights only.

Musical drill at the “Native Elementary School” Palapye 1898 by Rev Willoughby (Botswana National Archives).

A mission school was built by Khama and run by Alice Young, and soon 190 children were attending in four classrooms. [11]

Three Chiefs travel to England

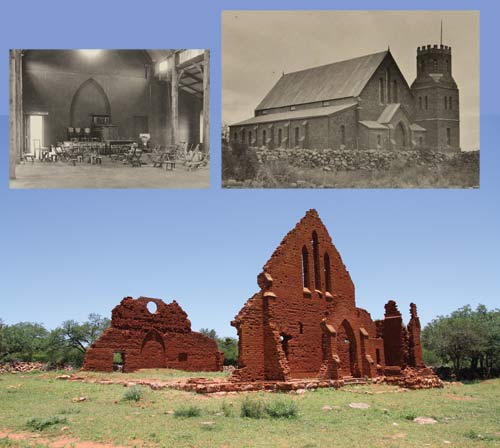

Studio portrait of the three chiefs and Willoughby as they appeared in the (London) Illustrated News Sept 21 1895, the “Three Dikgosi” memorial in the CBD of Gaborone (2013), and photo of Khama and company setting off on the journey by Rev Willoughby (Botswana National Archives).

Jameson Raid

Shortly after Khama and Willoughby returned to Palapye, Jameson (a doctor-soldier-politician working for the BSAC), passed through on his way South. Jameson admonished Khama for going to England:“You had no reason to distrust the Company and you had no right to go to England in the way you did”

“Dr Jameson” replied Khama, “you have got a smooth tongue, but if, as you say, I should have relied on your friendship and peaceful intentions, can you tell me why these big guns are here? What is the object of their movement ? Are they not a sign of destruction and death ? Please do not try to hoodwink me – I am not a child!”

“Oh no, no Khama! “ protested Dr Jameson, “I am going to Mafeking on important business and I am taking these guns down with me to have them repaired”

“No doctor” maintained Khama, shaking his head, “I am not blind, I can see this is a military expedition”. [13]

Khama was of course correct, and Jameson led the disastrous raid into South Africa days later. His forces were made to surrender, and Cecil Rhodes, who had backed the incursion was obliged to resign as Prime Minister of the Cape Government. This led to the British government dropping any plans they may have had to hand over the protectorate to the BSAC.

Railway

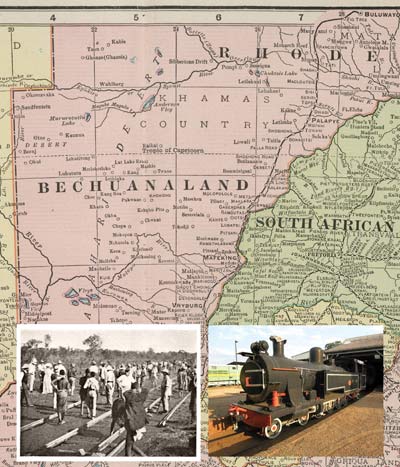

1901 map published by George Cram showing the railway line. It incorrectly shows both Shoshong and Palapye as being on the railway line. Note “Shoshong Road” station on the Tropic of Capricorn. Inset: Laying track north of Palapye at half a mile a day (Rhodesia Railways), Class 6 steam locomotive at Bulawayo Railway Museum (Photo by Geoff Cooke).

References

[1,2] Knight-Bruce W (Mrs) (1893) “The Story of an African Chief – Being the Life of Khama.” Kegan, Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co Ltd[2] Cape Argus 23rd October 1890

[3] Lloyd E (1895) “Three Great African Chiefs, Khame, Sebele and Bathoeng.” T.Fisher Unwin, London

[4] Blackbeard S (1930) “Memoirs of Samuel Blackbeard.” Botswana Notes & Records Vol 17 (1985)

[5] Hepburn J.D (1895) “Twenty Years in Khama’s Country.” Hodder & Stoughton

[6,10,11,14] Rutherford J (2009) “Little Giant of Bechuanaland – A biography of William Charles Willoughby Missionary & Scholar.” Mmegi Publishing House

[7] Campbell A (2008) “Khama III, Missionaries and Old Palapye Church Building.” Botswana Notes & Records Vol 40

[8] Harris J C (1922) “Khama the Great African Chief” Livingstone Press, London

[9] Bryden H.A (1891) “On the present Distribution of the Giraffe, South of the Zambesi, and on the best means of securing living Specimens for European Collections” Proceedings of The Zoological Society of London 1891:445-447 (1891) http://biostor.org/reference/108094

[12] Parsons N (1998) “King Khama, Emporer Joe & the Great White Queen.” The University of Chicago Press

[13] Grant Sandy (2012) “Botswana: An Historical Anthology.” Melrose Books www.melrosebooks.co.uk