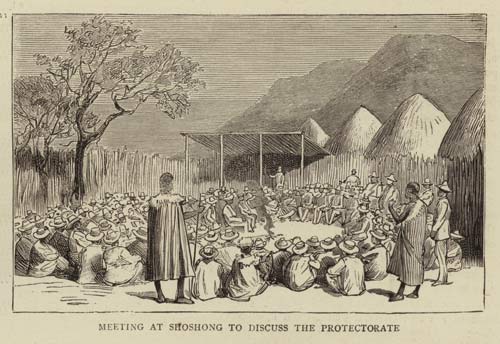

Protectorate

In 1882, John Mackenzie left Kuruman station and returned to England where he tried to influence opinion in favour of British protection to Bechuanaland. This was the time of the “Scramble for Africa” when England, France, Belgium and Germany were dividing up Africa and seeking to exploit its mineral and other wealth.

Cecil Rhodes of the British South Africa Company (BSAC) was a major player in this, and saw the Missionaries’ Road as a “Suez Canal” from the British Cape Colony up to Central Africa – a British wedge between German South West Africa and the Transvaal Republic.

In 1884 Cecil Rhodes declared:

Bechuanaland is the neck of the bottle and commands the route to the Zambesi. We must secure it, unless we are prepared to see the whole of the North pass out of our hands, .. I do not want to part with the key of the interior, leaving us settled on this small peninsula. [1]

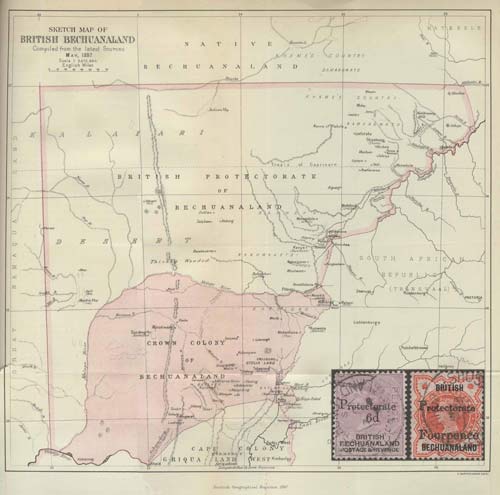

map of the Protectorate which originally stopped at 22° latitude but was soon extended further north to the current Botswana border (from Mackenzie (1887). Inset: stamps from the period.

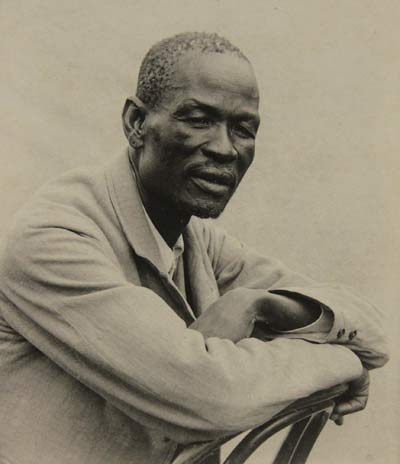

I have to say there are laws of my country… which …I wish…should … not be taken away by the Government of England. I refer to our law concerning intoxicating drinks... I refer further to our law which declares that the lands of the Bamangwato are not saleable. I say this law also is good; let it be upheld and continue to be law among black people and white people.

[2]It is clear that the Batswana and the British had different ideas about the protectorate, and that the British were acting more to safeguard their trading routes and to prevent expansion by the Germans and Boers than from a desire to protect the Batswana people.

In 1882-3, shortly after the death of Sekgoma and while Khama was away at Boteti, Kgamane, who had been left as governor of Shoshong, lifted the alcohol ban and ordered the revival of the initiation schools in a bid for power. However, he failed and fled in 1883 when Khama returned. [3]

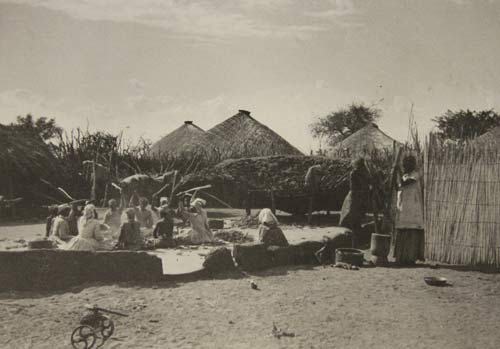

A new missionary, Edwin Lloyd, arrived in 1887, and records that members of the Bakaa were again living in the village. [4] The total population was estimated at around 15,000. One of the impacts of the protectorate status was a boundary commission which ruled on a dispute about some wells used for watering cattle at Lephepe (70 km SW of Shoshong) which were claimed by both the Bakwena and Bangwato people. The ruling was that the wells should be shared. [5]

Khama had clearly been considering the need to move to a new capital, and indeed having stayed in one place for nearly forty years was highly unusual. The formation of the protectorate gave confidence that the Matebele raids were no longer such a threat, and this together with the fact that the water supply was poor in Shoshong and people were living in insanitary conditions probably led to his decision to move. [6]

Since then, Shoshong itself has passed away, and only a few ruins are left of all its crowded life. The springs in the kloof dried up more and more, and after the English alliance it was less necessary to cling to the mountains as a fortress in Matabele raids...

[7]

References

[1] Zins (1997) “The international context of the creation of the Bechuanaland Protectorate in 1885” PULA Journal of African Studies. vol. 11. no 1 (1997)[2] Mackenzie J (1887) “Austral Africa; Losing it or Ruling it” London

[3] Parsons N (1973b) “Khama III, The Bamangwato, And The British, With Special Reference To 1895-1923” PhD Univeristy of Edinburgh

[4,5] Lloyd E (1895) “Three Great African Chiefs, Khame, Sebele and Bathoeng.” T.Fisher Unwin, London

[6] The phrase “indescribable filth” is used by several modern writers, but I have not been able to find it in a contemporary source, although Lloyd (1895) notes that Khama “left his old town partly for sanitary reasons”.

[7] Knight-Bruce W (Mrs) (1893) “The Story of an African Chief – Being the Life of Khama.” Kegan, Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co Ltd