Sekgoma

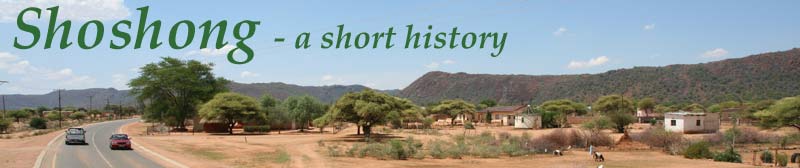

Meanwhile, Sekgoma established the Bangwato capital on the site of modern Shoshong in 1850. In 1851 there were about 900 huts. [1] Sekgoma attacked and incorporated other tribes such as the Babirwa and Balete during this period, joining the Baphaleng, Batalaote, Basarwa and others including the Makalaka (a term for those dispossessed by the Matebele). [2] By 1852 there were about 3,000 huts, with people all seeking refuge from the Matebele raiders.

James Chapman, a trader, passed through Shoshong in 1852 and noted; The following day we got permission to leave, and being visited by the eldest son of Sekomi, a lad of about sixteen, of very prepossessing appearance, I dressed him out in a suit of my own, and presented him with a nice grey pony, to the delight of the natives generally. I thus established myself, quite unintentionally, in the position of mate, or bosom friend, to Sekomi�s heir �and I was known only as �Chapman Kala�, or �Khama� � which name I have retained ever since in these regions. [3]

Livingstone passed through the Shoshong area for the last time in 1853 on his first major expedition to Luanda in Angola. He returned by foot and �discovered� the Victoria Falls in 1855 before going on to explore the Zambezi and Lakes Nyasa and Tanganyika until his death at Ujiji, Tanzania in 1873.

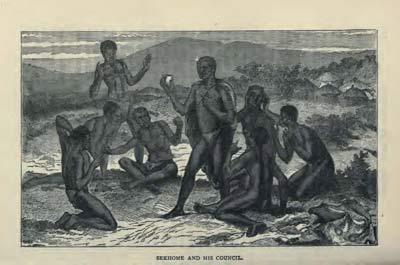

In 1857 Sechele orchestrated the replacement of Sekgoma as kgosi by his half brother Macheng (see later) but he was deposed and Sekgoma returned to power just two years later. [4]

Mission station

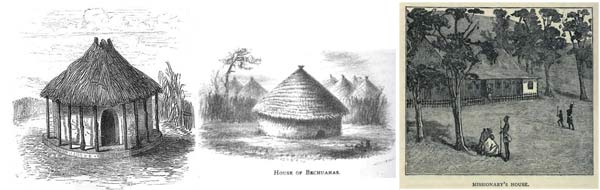

In 1859, Rev Heinrich Schulenburg, a German Lutheran missionary from the British colony of Natal, opened a school in the village. He educated Khama, his brother Kgamane and Khama�s future wife Mogatsa Motswasele (Mma Bessie). In 1860 Khama was baptised, and in 1862 he was married. Then in 1862 John Mackenzie and his wife, and Roger and Elizabeth Price of the London Missionary Society (LMS) came to Shoshong and after a period of working with the Lutherans, by mutual consent the Lutherans left in 1863.In his book �Ten years North of the Orange River�, John Mackenzie gives this description:

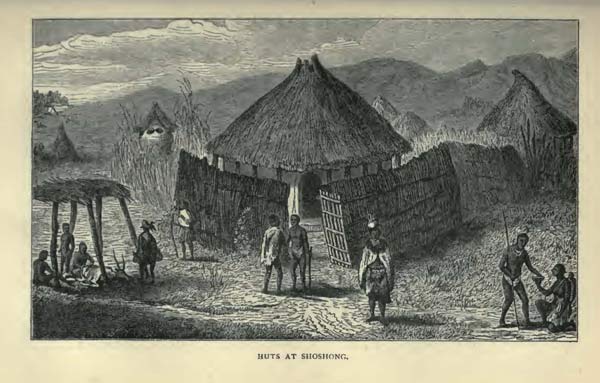

Shoshong, the town of the Bamangwato, contains a population of some 30,000. It is situated at the foot of a mountain range of primary rock stretching from east to west for more than a dozen miles. About three miles to the south of this range there is another basaltic mountain called Marutlwe...

The ground lying between the hills is occupied by the gardens of the Bamangwato. The main town spreads along the foot of the mountain, and some distance along the gorge in the mountain range, where the stream flows which supplies the town with water. There are also five divisions of the town in a beautifully sheltered position among the mountains.

Again, there are small towns along the range to the west to the distance of some six miles, all being under one chief, whose decision in every case is final. The most distant villages are those of Makalaka refugees, who fled recently from the enormities of the Matebele sway. They chose to remain at a distance from the large town for the sake of their gardens, for it takes some of the Bamangwato who reside in the large town more than an hour to reach their cultivated fields...

Lions have twice attacked live stock at the town of Shoshong during my residence there; and once my own cattle-post was attacked by two lions, and four oxen were killed. A letshulo is ordered out on such occasions; the lion is surrounded and put to death. [5]

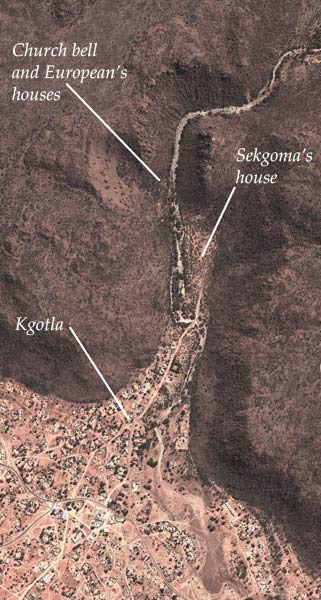

The Europeans lived in a separate part of the village on the west side of the riverbed, while Sekgoma lived on the east side. Some ruins of the houses can still be seen, the area now being known as �Old Shoshong�.

Matebele Raids

In March 1862 Matebele raiders were seen approaching Shoshong, and Kgosi Sekgoma ordered women and children into the mountains. [6] Khama and Kgamane led around 200 men, the majority with guns and about eight on horseback, to repel the attackers. The Matebele were armed with spears and shields, and initially it went with Khama, but a group of Matebele crept round unseen and ambushed Khama from behind. The Bangwato fled back to Shoshong leaving about 20 dead, the Matebele losses being much greater. Later that night the Matebele attacked Shoshong from the south side, but after taking some goats and destroying outlying crops they retreated. In response Sekgoma sent out a party to raid the Matebele cattle posts.

Initiation

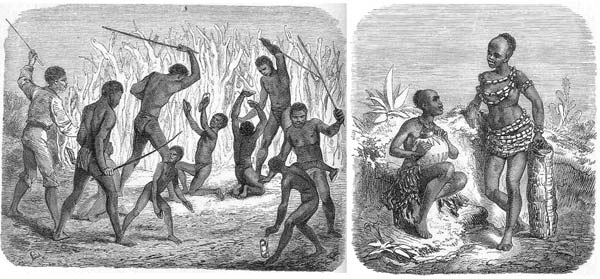

A very important part of tribal life was the initiation schools which marked the passage of boys and girls to adulthood. The schools (�bogwera� for boys and �bojale� for girls) typically took place in February/March every four years, or when a kgosi�s son or nephew had reached a suitable age of around 9-16 years.Until they have undergone this process no youth was considered a man and no woman was considered of marriageable age. As part of the preparation for bogwera boys and girls were smeared with white chalk. The girls wore nothing but belts made of pieces of reed or aprons of genets� tails, their breasts and faces also whitened with chalk. The solemnisation of the rite took place outside the town, dingaka and old men acting as operators with the boys and old women with the girls.

Singing as they go, the young people of both sexes, accompanied by the [dingaka], would proceed beyond the town to the appointed spot, where the boys are put through a drill in manly exercises, and the girls are formally initiated into domestic duties, such as carrying wood and fetching water. [7]

The European explorer Holub also observed the boys being marched off in detachments to the kgotla, where:

Bare of all clothing, except their little girdle and their sandals, which they are permitted to hold in their hands, they are placed in two rows, back to back, and made to kneel down whilst a man, generally their next-of-kin, stands in front of each and proceeds to deliver his lashes, which the lads parry as best they can by the dexterous manipulation of the sandals; they are required to keep on singing, and to raise each foot alternately, marking the measure of the chant. [8]

The rite also included circumcision and hunting excursions and lasted around three months. It was not unusual for boys to die during the process. [9]

The group of initiates then became a regiment (mephato) who would work and fight together for the rest of their lives. A man would describe his age according to which regiment he belonged to.

While some missionaries were curious and respectful of Setswana customs, all were against polygamy and put pressure on converts to abandon some old customs such as the initiation ceremonies.

Khama went through the initiation process before the missionaries arrived in Shoshong, but after his conversion was against the custom and this became a cause of argument with his father Segkoma, when Khama�s brothers did not attend the initiation because they were at school.

At school, they were taught by Elizabeth Lees Price who noted in her memoirs that in 1863 her classes were so popular that �some students write on broken boxes and planks and others generally sit on the floor. Khama always does.� [10]

By 1865, the Prices and Mackenzies were conducting three schools in Shoshong with eight Africans as assistants, six of whom were Sekgoma�s sons. John Mackenzie records that he requested permission from �the chief of the Mapaleng� before teaching children �in his town� showing that the various tribes still had some autonomy. [11]

Elizabeth Price wrote of the smallpox epidemic in the early 1860�s when many died despite attempts by John Mackenzie to inoculate people.

Many horrible things do we hear in that valley at home, about wolves [hyenas] and their ravages. The smallpox and measles have raged lately, many and many a dead body was dragged out and left unburied without the town or up the sides of the hills and the wolves are ravenous thereabouts for human flesh so that women and children are ever and anon being carried off. [12]

References

[1] Morion B (1993) �Pre-1904 Population Estimates of the Tswana.� Botswana Notes & Records Vol 25[2,5,6,11] Mackenzie J (1871) �Ten Years North of the Orange River.� Edmonston & Douglas

[3] Parsons N (1971) �Independency and Ethiopianism among the Tswana...� School of Advanced Study

[4] Parsons N (1973) �Khama III, The Bamangwato, And The British, With Special Reference To 1895-1923� PhD Univeristy of Edinburgh

[7] Willoughby WC (1905) �Notes on the Totemism of the Becwana.� Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain & Ireland Vol 35

[8] Holub E (1881b) �Sieben Jahre in S�d-Afrika (Seven Years in South Africa).� Alfred Holder

[9] Lloyd E (1895) �Three Great African Chiefs, Khame, Sebele and Bathoeng.� T.Fisher Unwin, London

[10,12] Price E.L (1956) �The Journals of Elizabeth Lees Price�, Una Long, ed.